|

Murray Kaufman was a showbiz kid. His mother and aunt played in vaudeville, mom as a pianist, his aunt as a performer, and Murray himself appeared (as one of many child extras) in several Hollywood films of the 1930s. As the only child of a demanding mother, Murray always strived to make her proud, though she had little patience for parenthood and packed him off to a military boarding school.

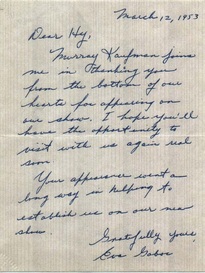

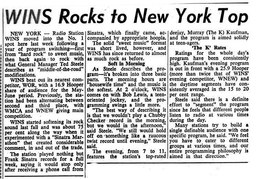

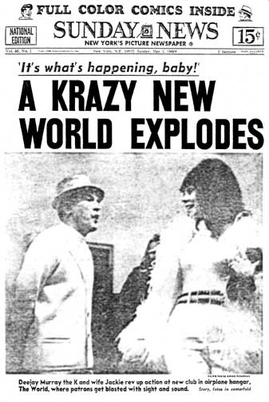

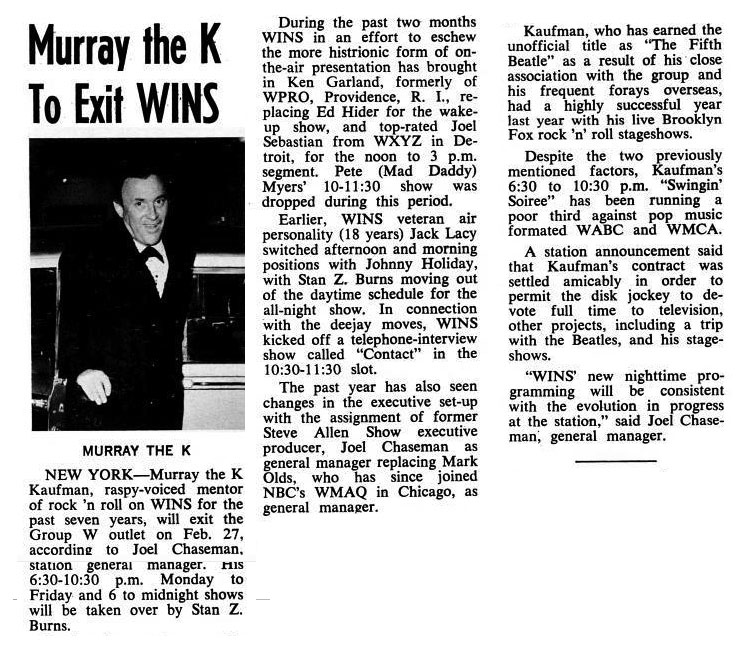

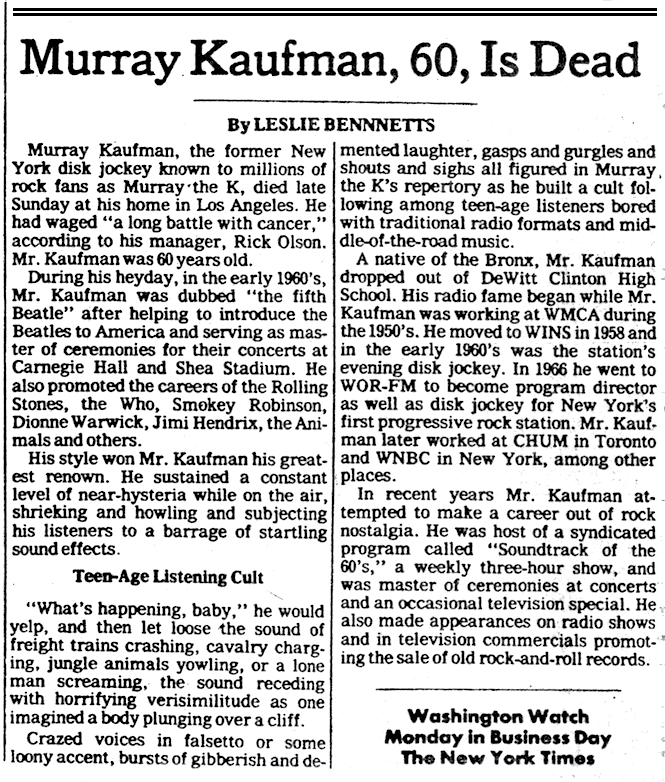

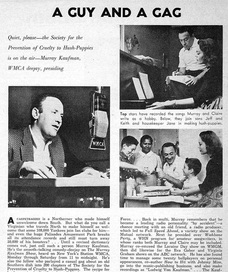

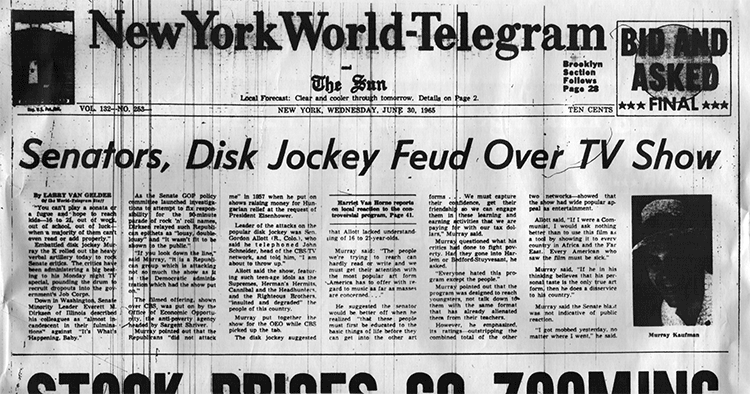

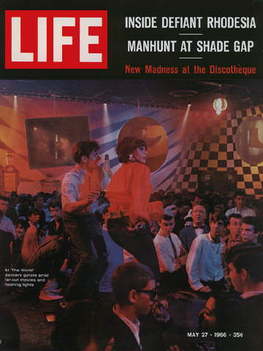

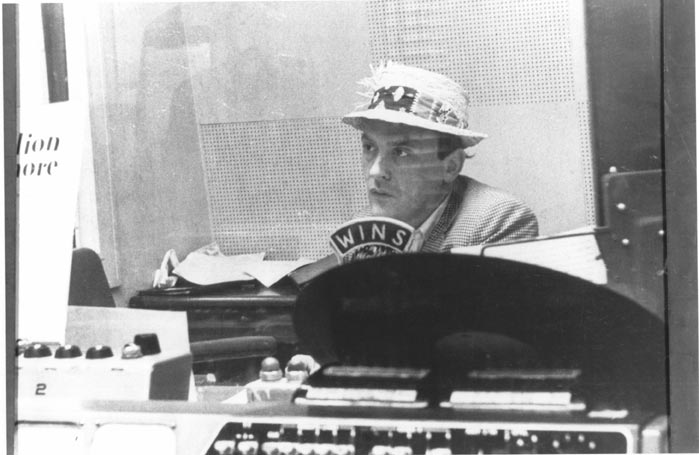

When real military service came along, Murray couldn't quite pull off a Section 8 discharge and wound up organizing entertainment for the troops. It was an assignment that gave him a headstart at putting together shows -- after World War II -- for the resort hotels in New York's Catskill Mountain Borscht Belt. In the off-season, Murray left the mountains and returned to Manhattan, where he had been born in 1922, and held an assortment of jobs in advertising and music promotion. As a song plugger for Bob Merrill and, specifically, Merrill's early '50s hit “How Much Is That Doggie In The Window,” Murray seemed to have found his stride. By 1953, he was producing late night interview programs from a club on Lexington Avenue. The program was hosted at various times by Eva Gabor, Laraine Day, and Virginia Graham. It was that experience that led to a nightly show of his own, which occupied the two hours before Barry Gray's midnight program and which, in an era when husband-and-wife shows reached the height of their popularity, was frequently co-hosted by his “better half.” During that same stint, Murray became president of the National Conference of Disk Jockeys. The organization, which sought to raise the image of the broadcasters who catered to a younger listening audience, included Dick Clark on its executive board and, in 1957, spearheaded a relief effort for refugees of the Hungarian Revolution. From WMCA, Murray went briefly to WMGM, developing the late night shtick that reached its peak a year later at WINS. As the overnight host of “The Swinging Soiree,” Murray built a following that readily tuned in earlier... after Murray assumed Alan Freed's primetime slot, following Freed's untimely fall from grace during the payola scandals. From mid-1958 until the sale of WINS to Group W and its conversion to an all news format in 1965, Murray the K was the king of the New York City airwaves. Murray's antics on the air, on the streets, in the subways, and overhead (broadcasting from Air Force jets), combined with his natural showmanship to earn him a virtual franchise in live events. As the host of personal appearances by hot bands (usually at local movie theaters) or as the emcee of four-times-a year rock 'n' roll shows at the Brooklyn Fox Theater, Murray developed the first truly multi-racial audience. Like Freed before him, Murray Kaufman believed in the talents of black and Latin artists and preferred to play their records rather than the cover versions recorded by white singers. By building preference for a wide variety of music on the air (including Frank Sinatra, whose music opened every show), Murray attracted fans from every level of society to his live shows and, in their passion for the music, tensions had virtually no opportunity to develop. Kaufman went live in other ways. He became the unofficial American spokesman for the Beatles, thanks to touring American groups who were the opening acts at Beatle concerts in Great Britain (before the group arrived in America). When Brian Epstein asked for advice, those performers advised Brian Epstein to get in Kaufman's good graces if he wanted the Beatles to succeed in the States. New York was the market they had to own and, in the ratings at least, Kaufman owned New York. Of course, once the Beatles arrived, Murray and the group were inseparable. He broadcast from their hotel room, accompanied them to their first show in Washington, D.C., co-hosted their second show at Carnegie Hall, and went with them to Miami for the third leg before joining them in England and emceeing a Wembley Stadium concert. At that concert, he also met the Rolling Stones, suggesting later that they cover an American R&B hit "It's All Over Now " which became their first number one hit in the States. It was Murray's popularity that led the Federal government's Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) to approach him about producing a national program that would a) appeal to inner city youngsters and b) let them know about job opportunities through the New Chance program. The show, It's What's Happening, Baby, which was arguably (fifteen years before MTV) the first music video, attracted national headlines, the censure of Congressmen who deplored the use of public funds to broadcast “jungle music,” and too many inquiries from young people about a government program that turned out to be woefully under-funded. Locally, Kaufman was innovative in other ways. He devised a new dance hall phenomenon that set the pattern for Manhattan's Cheetah and San Francisco's Fillmore Auditorium. In an abandoned airplane hangar at Long Island's Roosevelt Field, the starting point of Lindbergh's historic trans-Atlantic flight, he created Murray the K's World, a multi-level, multi-media discotheque that combined live and recorded music with projected slides and film, providing a level of sensory overload that only Timothy Leary seemed able to exceed... with the help of mind-altering drugs. As the World was taking off (and quickly crashing), WINS was changing formats. There was no more room for Murray the K and his cronies. Times were changing. The first threat was Top 40, a format which was considered before Group W decided to convert WINS to "all news all the time." For someone like Murray, Top 40 was oxygen debt, cutting off the creative freedom to program his own show, choose his own music, take his own risks -- like the time he refused to play the A side of Dionne Warwick's new record because he was convinced that the B side would prove to be the hit. In spite of calls from everyone connected with Scepter Records, Dionne's label, Murray played the B side -- "Walk On By." Within a year, Murray was leading a group of disillusioned talent to a new frontier -- FM rock. On WOR-FM, Murray set the tone for the rest of the '60s. He played records from albums, not singles, so that Bob Dylan's "Positively Fourth Street" and Janis Ian's "Society's Child" were aired in full (one of the few places they could get played at all, initially). At the same time, Kaufman was extending his OEO experience to produce local television specials that were combinations of on-location and in-concert performances punctuated with unexpected appearances by guests such as football great Joe Namath and the undisputed king of variety shows, Ed Sullivan. Less than twelve months later, when Bill Drake arrived to program WOR as an oldies-format station, Murray and the others quickly left. Not, however, before Murray told his listeners, as he had at WINS, just exactly what the executives were planning to do... before the executives had alerted the press. It won him few friends in a town where everyone in the industry knows everyone else in the industry and where disloyalty is as ominous as a Mafia kiss. Thanks to WINS' nightly 50,000 watt clear-channeling transmitter, Murray's reputation reached far beyond the boundaries of metro New York. For awhile, he aired in Toronto, then in Washington and Maryland before returning, in the early 1970s, to a national stint on NBC's Monitor and, subsequently, to a regular program on WNBC. That relatively low key show, which led into Wolfman Jack's late night program, declined along with Murray's health at the start of a long fight with cancer. His last New York gig was in 1975 on the extremely mellow WKTU, a station he willingly left to serve as a consultant on the production of Beatlemania. Following a national promotional tour, Murray left New York for "the Coast" to accompany his soon-to-be sixth wife, a soap opera star whose show relocated to L.A. It put him in an ideal position to host Watermark's syndicated Soundtrack of the '60s, which carried Murray's name and reputation to markets as far away as Australia. Yet Kaufman's battle with cancer was a losing one. By the end of one season, he had to withdraw from Soundtrack, giving up his slot to Gary Owens. Within a year, at the age of 60, Murray Kaufman was dead. Yet his legacy lives on through the artists whose careers he advanced (from Bobby Darin and Dionne to The Rascals and The Who), the innovations he brought to music broadcasting, and the thundering call of the Submarine Race Watchers -- Ah bey! |

|